17. 4. – 19. 4. 2026

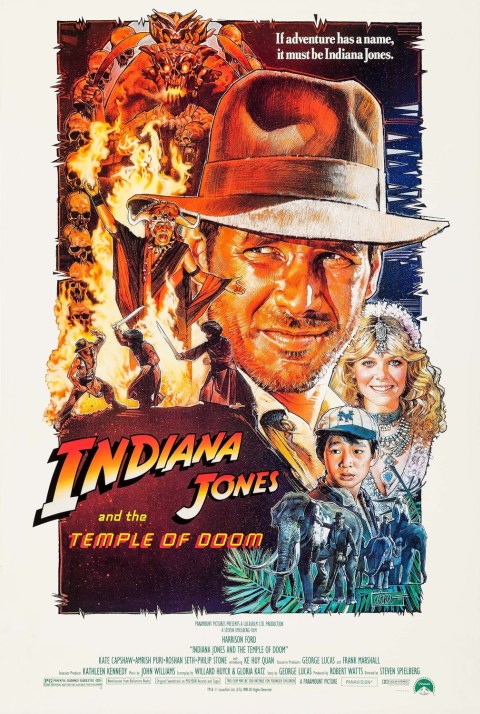

Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom

Original title: Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom

Original title: Indiana Jones and the Temple of DoomDirector: Steven Spielberg

Production: 1984, USA

Length: 118 min.

Screened:

KRRR! 2012: 70mm 2.2:1, Colours intact, MG Dolby, Spoken language: English, Subtitles: CzechAnnotation for KRRR! 2012

After the great success of the first adventure of the intrepid archaeologist Indiana Jones in the film Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981), director Steven Spielberg and producer George Lucas decided to follow up with a sequel, Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (1984), which is, however, a somewhat unconventional sequel.

Firstly, it takes place before the Conquerors. Secondly, apart from the main character, none of the other Conquerors appear in it. Thirdly, although Indy wears a hat, cracks a whip, is afraid of snakes and travels the world in search of rare artifacts of human history, he otherwise does not resemble himself from the previous film in terms of character. Fourthly, the film refers to completely different cinematic or literary predecessors, which aesthetically distinguishes it from the previous film. And it is precisely the last-mentioned point that I will focus on in the following lines.

The second Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom, together with the fourth Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull (2008), belongs to the half of the "Lucasberger" film series that is less popular with viewers. However, this fact does not speak so much about their lack of quality as about the clash of artistic concept with the idea of a "good story told". Both of them reflect the volatile encyclopedic nature of the Jones series even more extreme than the other two, when the form of the films is based on quoted patterns - which is especially true for Temple of Doom. The conquerors drew on those well-known to Western viewers: films about the (inter)war period, westerns, biblical films or oriental adventure stories. But Temple of Doom offers adventures of a Burroughsian (Tarzan), Kiplingian (Jungle Books) or Salgarian (Sandokan) nature, where African or Indian motifs are mainly used, and realistically motivated elements are freely combined with "irrational" Eastern mysticism.

The insidiousness of Temple of Doom lies mainly in the frantic collage-like nature with which these - in themselves more difficult to accept - motifs are arranged one after the other, without the Western viewer being given the opportunity to experience the certainties of their own Euro-American world for at least a moment. The thoughtful homage to Eastern culture-smeared junk begins with a ludicrously dizzying exposition, in which a Busby Berkeley musical, a grotesque crowd scene in an Obi-wan bar, a bizarre city chase, a fall from a plane on an inflatable boat, a ride down a snowy slope, etc.

The viewer is driven at a relentless speed from the urban environment to exotic India, where the certainties of Western culture end, physical assumptions do not apply, evil pagan cults reign and magic spells or dark hypnosis are at work. Just as the means of transport are constantly changing in the action exposition, the modes of narration and genre formulas (including Hollywood screwball comedy) continue to change, with the pace of individual sequences not following the classic rhythm of "slower-faster-slower-faster", but rather "fast-fast-fast-slow-slow-fast-fast-fast". The constant flow of exotic stimuli, shocking elements, dizzying action attractions, dark environments and ruthlessly black humor thus evokes disturbing and even tiring feelings. Unfortunately, these distract from the impressive filmmaking awareness and self-confidence of the film, which would have completely fallen apart narratively and motivically in many others, but under Spielberg's solid direction, it is still a fascinating - if sometimes deliberately ugly - experiment with the genre, stylistic and narrative possibilities of action cinema.